Introduction & The Burnout Truth

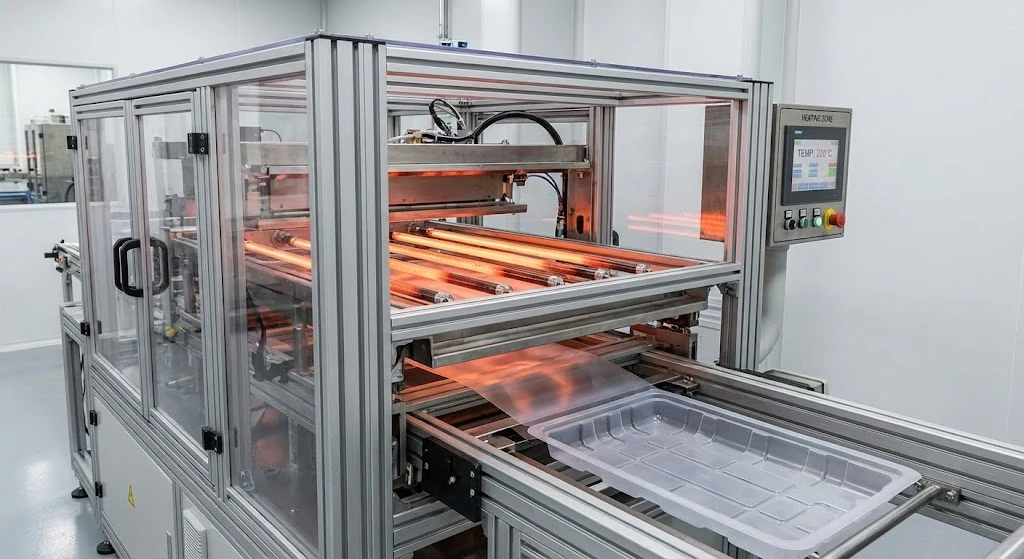

A common scenario in industrial automation: You specify a set of high-power infrared emitters for a new thermoforming oven. The manufacturer guarantees a 5,000-hour lifespan. However, after less than 300 hours of continuous operation, the lamps shatter, or the internal filaments snap.

You immediately suspect a manufacturing defect. However, in 90% of these cases, the failure is not metallurgical; it is mathematical. The system suffered from an overload in the quartz heater watt density.

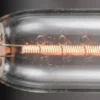

In thermal engineering, watt density is defined as the electrical power dissipated per unit of surface area of the heating element, typically expressed in W/cm^2 or W/in^2. It is the single most critical physical parameter in infrared oven design. It dictates the emitter’s peak surface temperature, its spectral wavelength output, and ultimately, its expected lifespan before catastrophic failure.

Before running the thermodynamic calculations to determine your maximum power threshold, ensure you have selected the correct wavelength for your target material by reviewing our Industrial Quartz Heating Tubes: The Complete Engineering Guide.

The Fundamental Equation: Defining the Active Heating Area

1. The Core Formula

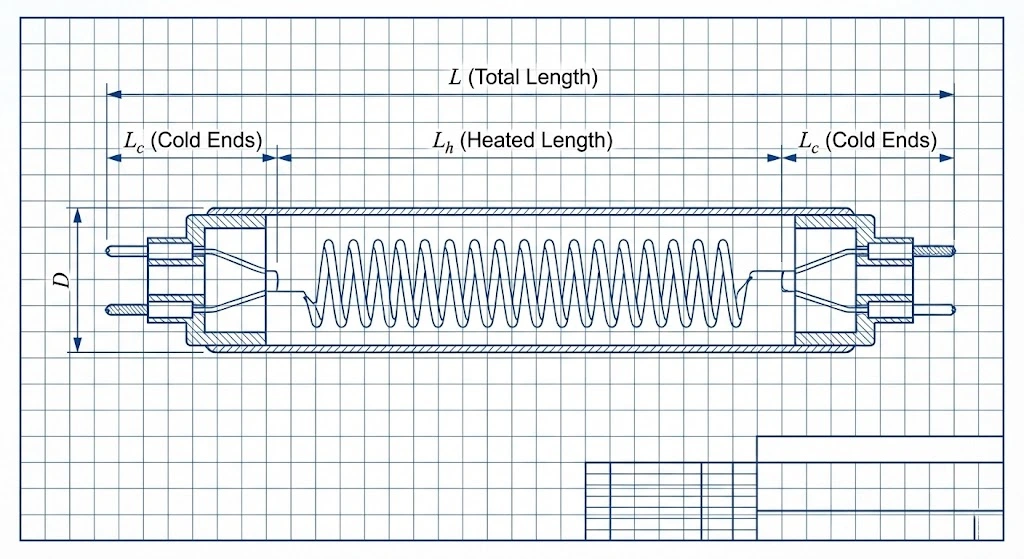

To calculate the quartz heater watt density accurately, we must isolate the active radiating surface area of the cylindrical tube. We do not use the entire physical length of the object; we only use the area actively emitting radiation.

The standard engineering formula is:

Wd = P/(π*D*Lh)

Where:

- Wd = Watt Density (W/cm^2)

- P = Total Electrical Power in Watts (W)

- D = Outside Diameter of the quartz tube in centimeters (cm)

- Lh = Heated Length of the tube in centimeters (cm)

2. The Most Common Engineering Mistake

The most frequent error junior engineers make is using the Total Length (L) of the quartz tube in the denominator instead of the Heated Length (Lh).

Every industrial infrared heating tube features “Cold Ends” (Lc) where the electrical connections and molybdenum foil seals are located. These sections do not contain the active tungsten or carbon filament and do not generate radiant heat. If you use the total physical length in your surface area calculation, you will artificially inflate the denominator, resulting in a falsely low calculated watt density.

- The Consequence: You will design an oven that runs dangerously hotter than your math predicted. The equipment will exceed the softening point of silica glass, leading to rapid filament burnout, devitrification, or localized fires.

Material Limits: Maximum Safe Watt Densities

Not all infrared technologies can handle the same thermal stress. The physical limits are dictated by the filament material, the inert gas fill, and the quartz envelope thickness. Pushing a heater beyond its specific limit guarantees failure.

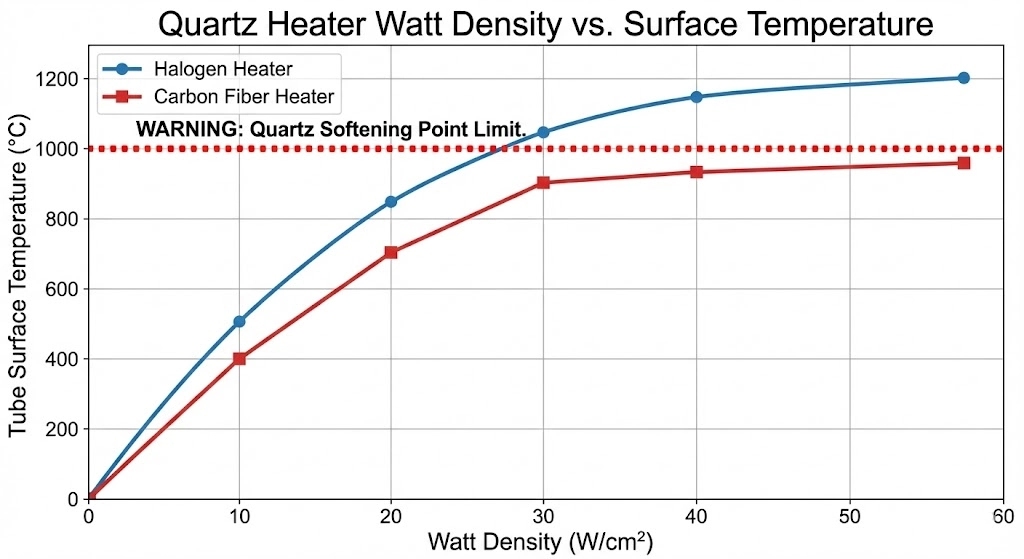

1. Halogen Tungsten Emitters (Short Wave)

Because halogen tubes utilize a high-pressure halogen gas cycle that actively redeposits evaporated tungsten back onto the filament, they can survive extreme internal temperatures (operating near 2400K).

- Safe Limit: Halogen emitters can typically operate at extreme quartz heater watt densities of 40 to 60 W/cm^2. This makes them the definitive choice for high-speed, high-density applications like PET blow molding or rapid metal annealing.

2. Carbon Fiber Emitters (Medium Wave)

Carbon fiber filaments operate at much lower color temperatures (approximately 1200K) to emit the highly absorptive medium-wave radiation perfect for curing plastics and drying water-based paints. They lack a regenerative gas cycle and rely on a strict vacuum or inert gas environment to prevent oxidation.

- Safe Limit: To ensure the rated 6,000 to 8,000-hour lifespan and maintain the soft radiant output, carbon fiber tubes should be strictly restricted to a watt density of 15 to 25 W/cm^2.

3. The Gold Reflector Factor

Crucial Engineering Note: If you specify a tube with an integrated Half-Gold Reflector, you must immediately derate your calculations. The gold layer reflects 95% of the rearward radiant energy back through the filament and the front glass wall. This significantly increases the localized internal temperature of the quartz tube.

- Adjustment Rule: The maximum safe watt density for a gold-coated tube must be reduced by 15% to 20% compared to a clear, bare tube of the exact same physical dimensions.

Surface Temperature & Thermodynamics

1. Theoretical Foundation: The Stefan-Boltzmann Law

Once you establish your watt density, you must predict how hot the external surface of the quartz tube will get. The relationship between radiated power and absolute surface temperature is governed by the Stefan-Boltzmann Law:

P = ε*σ*A*(T^4 – T0^4)

Where:

- P = Net radiated power (W)

- ε = Emissivity of the material (Quartz glass is roughly 0.93 in the IR spectrum)

- σ = Stefan-Boltzmann constant (5.67*10^{-8}*W*m^{-2} *K^{-4}

- A = Surface Area (m^2)

- T = Absolute temperature of the emitter in Kelvin (K)

- T0 = Ambient temperature of the surroundings in Kelvin (K)

The engineering reality extracted from this equation is severe: Surface temperature increases proportionally to the fourth root of the watt density. If you want to double the radiant heat output, the internal filament temperature must increase exponentially, pushing the materials closer to their absolute physical limits.

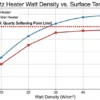

2. The Engineer’s Cheat Sheet (Free Air Approximation)

Solving the fourth-order polynomial for every minor design iteration is inefficient. For a standard 10mm or 12mm quartz tube operating in “Free Air” (natural convection at 25°C ambient), thermal engineers rely on established empirical data curves.

Environmental Variables: The 3 Derating Factors

Paper calculations assume a perfect laboratory environment. Real-world industrial ovens introduce harsh variables that will destroy a heater running near its maximum watt density limit.

1. Forced Convection (Air Cooling Systems)

If your manufacturing process involves high-velocity ambient air blowing across the heating tubes—such as in an automotive paint drying booth or a paper mill drying web—the forced convection actively strips heat away from the quartz envelope. In these specific scenarios, you can safely design a system with a higher watt density than the standard free-air curves suggest, as the airflow prevents the quartz from reaching its softening point.

2. Ambient Oven Temperature (The Closed Box Effect)

Conversely, if the heaters are installed in a highly insulated, sealed vacuum chamber or a dense curing tunnel, the ambient temperature (T0 in the Stefan-Boltzmann equation) rises rapidly. As the temperature delta (ΔT) between the heater surface and the surrounding air shrinks, the heater struggles to shed its energy. The internal temperature of the tube will skyrocket. Enclosed ovens require a significantly lower watt density design to prevent catastrophic thermal runaway.

3. Cold Pin Temperature Limits (The Ultimate Failure Point)

Hardcore Engineering Rule: The most vulnerable physical point of a halogen or medium-wave quartz heater is not the glass envelope; it is the molybdenum foil seal located inside the ceramic end caps (the Cold Pins).

- The Physical Limit: Molybdenum is used because its coefficient of thermal expansion matches quartz glass. However, if this molybdenum seal exceeds 350°C in an oxygenated environment, it will rapidly oxidize. The metal will swell, crack the quartz vacuum seal, allow oxygen into the tube, and instantly incinerate the tungsten filament.

- The Design Solution: If your application demands an exceptionally high quartz heater watt density, you must incorporate forced air cooling specifically directed at the ceramic end caps to keep those seals below the critical 350°C threshold.

Step-by-Step Calculation Example: Custom Thermoforming

Let’s apply these formulas to a realistic industrial engineering scenario.

The Scenario: A client is designing a compact, high-speed thermoforming machine for heavy-gauge plastic trays. They require a total power output of 3000 Watts. The physical space inside the machine restricts the total tube length to 800 mm, and the maximum allowable tube diameter is 15 mm. The engineering team has specified Carbon Fiber to match the plastic’s absorption spectrum.

The Calculation:

- Determine Heated Length (Lh): Assuming standard manufacturing parameters of 50 mm cold ends on each side of the tube.Lh = 800mm – (50mm*2) = 700 mm = 70 cm

- Determine Diameter (D): D = 15 mm = 1.5 cm

- Calculate the Active Surface Area (A): A = π*1.5 cm * 70 cm =329.87 cm^2

- Calculate Quartz Heater Watt Density (Wd): Wd = 3000 W / 329.87cm^2 = 9.09 W/cm^2

The Engineer’s Verdict:

At 9.09 W/cm^2, this design sits perfectly within the highly stable, efficient lower half of the 15-25 $W/cm^2$ maximum threshold for Carbon Fiber medium-wave emitters. The design poses no threat to the molybdenum seals and will easily achieve its rated 6,000-hour lifespan. The specification is Approved for Manufacturing.

FAQ: Common Thermal Engineering Questions

Is a higher quartz heater watt density always better for industrial heating?

No. Excessive watt density forces the emitter to operate at a much higher color temperature, which shifts the peak wavelength shorter. This not only wastes electrical energy by mismatching the target material’s absorption spectrum (heating the air instead of the product) but also severely degrades the operational lifespan of the heater. The optimal watt density is one that exactly matches your required process heat loss—no more, no less.

How do you lower the watt density of an existing infrared heater in the field?

If the machine is already built, you cannot change the physical dimensions (Diameter or Heated Length) of the tube. The only mathematical way to lower the watt density is to lower the Power (P). You achieve this by reducing the applied voltage using an SCR (Silicon Controlled Rectifier) Thyristor power controller. Lowering the RMS voltage drops the total wattage, thereby proportionally reducing the watt density and cooling the surface temperature.

What happens if the specified watt density is too low for the process?

If the watt density is specified too low, the emitter will lack the thermal “push” (radiant intensity) required to overcome the thermodynamic heat losses of the oven and the cold product entering it. The equipment will either fail to reach the designated setpoint temperature, or the pre-heating cycle will take far too long, causing unacceptable delays in the production line’s takt time.

Conclusion: Stop Guessing, Start Engineering

Exceptional thermal engineering is a strict, mathematical balancing act. Success in modern industrial heating lies in finding the exact intersection between applied voltage, physical geometry, watt density limitations, and material absorption curves.

Math doesn’t lie. Guesswork burns out heaters.

Do not let the cost of trial-and-error prototyping eat into your manufacturing margins. If you are designing a new thermal process, send your target temperatures, dimensional constraints, and material specifications to the Hongtai engineering team. With over two decades of applied thermodynamic experience, we will calculate the optimal quartz heater watt density for your application and output a comprehensive set of custom engineering drawings.

[Consult a Hongtai Thermal Engineer & Get Your Custom Calculation]